|

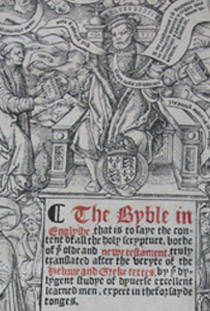

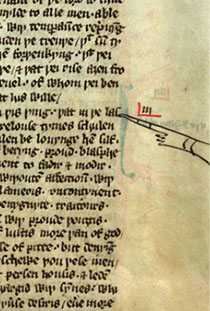

Title: St. Chad Gospels / Lichfield Gospels / St Teilo Gospels / Llandeilo Fawr Gospels. Item No.: MS Lich 01. Date: c. 730. Language: Latin; marginal writing in Latin, Old Welsh and Old English. Codicology: Written in iron gall ink on vellum. Script is Insular majuscule with some uncial characteristics. Text is written in single columns. Scribes used various efficiencies, including Insular Symbols, Nomina Sacra, Contractions, & Tironian Notae. Dry-point marginal writing. Rebound in: 17th century; 1707 (pages trimmed); 1862 (cut into single leaves); 1962, Roger Powell (pages flattened). Foliation: 236 folios + iv (added later). Dimensions: Binding: (L) 330 mm x (W) 262 mm; Spine: 65 mm; Foredge: 80 mm; Folio: (L) 317 mm x (W) 242 mm. Contents & Additions: The surviving text of the St. Chad Gospels includes the gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke 1-3:9. The rest of Luke and John are missing, as well as preliminary materials such as the Breves Causae (summaries of the gospels), Argumentum (information about the apostles), Canon Tables, and Jerome’s letter to Pope Damasus (explanation of the Canon tables). Added later: four handwritten pages of Boethius' Aristotelis In Categoriis, bound after the fourth end flyleaf and possibly used as the manuscript's cover prior to the eighteenth century; Notes - 1758, two pages; and Roger Powell's "Precis" on flattening pages and rebinding manuscript in 1961-62. Illuminations:

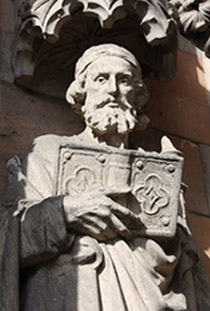

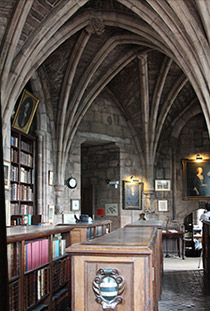

Provenance & History: Deciphering Provenance The St. Chad or Lichfield Gospels is an Insular Latin gospel-book produced in the 2nd quarter of the 8th century. The provenance of this book is less certain. Modern scholars have suggested four possible regions: Ireland, Northumbria, Wales, and Mercia (i.e., the kingdom responsible for founding Lichfield Cathedral). Some scholars have proposed Irish or Northumbrian origins due to the book’s shared paleographic and stylistic elements with the Book of Kells, Lindisfarne Gospels and Durham Cassiodorus. However, the Hereford Gospels, an 8th-century Mercian manuscript, also shares paleographic, textual, and stylistic features with the St. Chad Gospels. The similiarities between the St. Chad Gospels and its contemporary Irish and Northumbrian counterparts evinces a transculturation among Hiberno-Saxon cultures rather than a definitive provenance. Scholars have also suggested a Welsh provenance, pointing to the book’s Welsh marginalia. This prospect is exciting, since these marginalia respresent the oldest surviving examples of Old Welsh, but may be misleading in deciphering the book’s origin. The traces of Insular cultures within the St. Chad Gospels echo the fluid intercultural landscape of Anglo-Saxon England. Medieval Context: Mercia and Wales Diuma, Mercia’s first bishop (c. 655) was a Northumbrian priest from Ireland. St. Chad (c. 664-72), for whom Lichfield Cathedral was built, was Northumbrian and mentored by Aidan, an Irish monk who was also the first Abbott of Lindisfarne in Northumbria. Almost a century later, the St. Chad Gospels is a product of the intercultural Mercian landscape. Current extant material evidence suggests that this book was made in Lichfield. For example, its unique color palette can also be found in the Lichfield Angel. The Welsh marginalia attest to the book’s hundred-year residence at St. Telios Church in Wales. How the gospel-book ended up there remains a mystery, but material evidence suggests it was stolen from Lichfield during the first half of the 9th century. Missing preliminary folios suggest that the book was most likely taken for the precious metals decorating its cover, possibly in a Viking raid. The signature of Wynsige, the Bishop of Lichfield from c. 963-975, indicates that the book had returned to Lichfield by that time. Post-Medieval Context In 1646, the Lichfield Cathedral was sacked during the English Civil War. The latter part of the Gospels was presumably lost at that time. Precentor Higgins hid the surviving text from Cromwell’s forces and entrusted it to Frances, Duchess of Somerset, for protection. Frances returned the gospel-book to the Cathedral around 1672-73, along with 1,000 volumes from her household collection to help rebuild the Cathedral’s library. This gospel-book is still used ceremonially by the bishops of Lichfield for swearing oaths and in a limited number of liturgical roles by Lichfield Cathedral, such as in the procession of the Christmas service. References: Alexander, J.J.G. Insular Manuscripts 6th-9th Century. London: Harvey Miller, 1978. Benedikz, B. S. "Lichfield Cathedral Library: A Catalogue of the Cathedral Library Manuscripts," 3rd ed., Birmingham (1986). Brown, Michelle. “The Lichfield Angel and the Manuscript Context: Lichfield as a Centre of Insular Art.” Journal of the British Archaeological Association, 160.1 (2007): 8-19. ----. “The Lichfield/Llandeiolo Gospels Reinterpreted.” In: Kennedy, R. and Meecham-Jones, S. eds. 2008. Authority and Subjugation in Writing of Medieval Wales, pp. 57-70. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2008. Charles-Edwards, Gifford and Helen McKee. “Lost Voices from Anglo-Saxon Lichfield.” Anglo-Saxon England, 37 (2008): 79-89. Endres, Bill. "Digitizing Medieval Manuscripts: The St Chad Gospels, Materiality, Recoveries, and Representation in 2D & 3D.” Leeds: Arc Humanities Press, 2019. ----. "Imaging Sacred Artifacts: Ethics and the Digitizing of Lichfield Cathedral’s St. Chad Gospels.” Journal of Religion, Media & Digital Culture (JRMDC), 3.3(2014): 39-73. ----. "The St. Chad Gospels: Ligatures and the Division of Hands.” Manuscripta, 59.2 (2015): 159-86. Henderson, G. From Durrow to Kells: The Insular Gospel-books 650-800. London: Thames and Hudson, 1987. Henry, Françoise. Coloured pencil sketches of illuminations on pp. 5, 143, 218, 219, 220, 221. UCD Digital Library, Papers of Françoise Henry (1902-1982). Howlett, David. Insular Inscriptions. Dublin: Four Court Press, 2005. Hopkins-James, Lemuel J. The Celtic Gospels: Their Story and Their Text. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1934. James, Pamela. "The Lichfield Gospels: The Question of Provenance.” Parergon, 13.2(1996): 51-61. Jenkins, Dafydd and Morfydd E. Owen. “The Welsh Marginalia in the Lichfield Gospels, Part I.” Cambridge Medieval Celtic Studies, 5 (1983): 37-66. ----. “The Welsh Marginalia in the Lichfield Gospels, Part II: The ‘Surexit’ Memorandum.” Cambridge Medieval Celtic Studies. 7 (1984): 91-120. Lowe, Elias A. Codices Latini Antiquoiroes: A Palaeographical Guide to Latin Manuscripts Prior to the Ninth Century, vol. 2, Great Britain and Ireland, 2nd ed. (Oxford, 1972). Luster, Haley M. "Designing the Divine: A Perspetual Analysis of the Teilo/Chad Gospels at the Lichfield Cathedral Library." 2017. New Mexico State University. Thesis. Powell, Roger. "The Lichfield St. Chad’s Gospels: Repair and Rebinding, 1961-1962.” The Library, 10.4(1965): 260-265. Rodwell, Warwick, Jane Hawkes, Emily Howe, and Rosemary Cramp. “The Lichfield Angel: A Spectacular Anglo-Saxon Painted Sculpture.” The Antiquaries Journal. 88 (2008): 48-108. Scrivener, F.H.A. Codex S. Ceaddae Latinus, Evangelia SSS. Matthaei, Marci, Lucae Ad Cap. III. 9 Complectens. Cambridge: C.J. Clay and Sons, 1887. Stein, Wendy. The Lichfield Gospels. Ph.D. dissertation, Berkeley: University of California, 1980. Stevick, R.D. “The 4x3 Crosses in the Lindisfarne and Lichfield Gospels.” Gesta, 25.2 (1986): 171-184. |